New marine reserves raise a raft of questions for southern surfers as 10-year process finally bears fruit. We ask the experts how they even work, what implications there will be for surfing and fishing, and whether we should expect an increase in sharks over time.

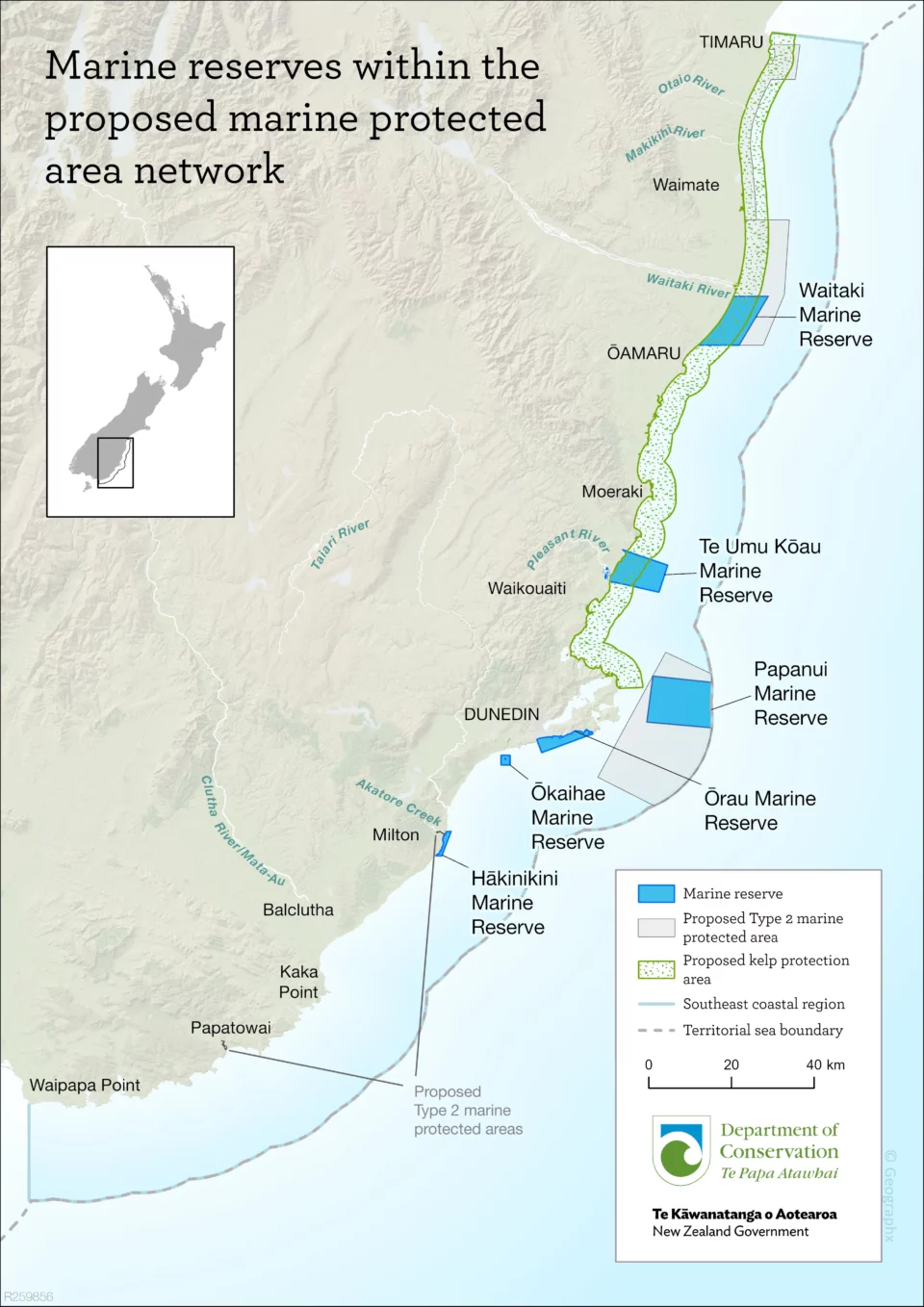

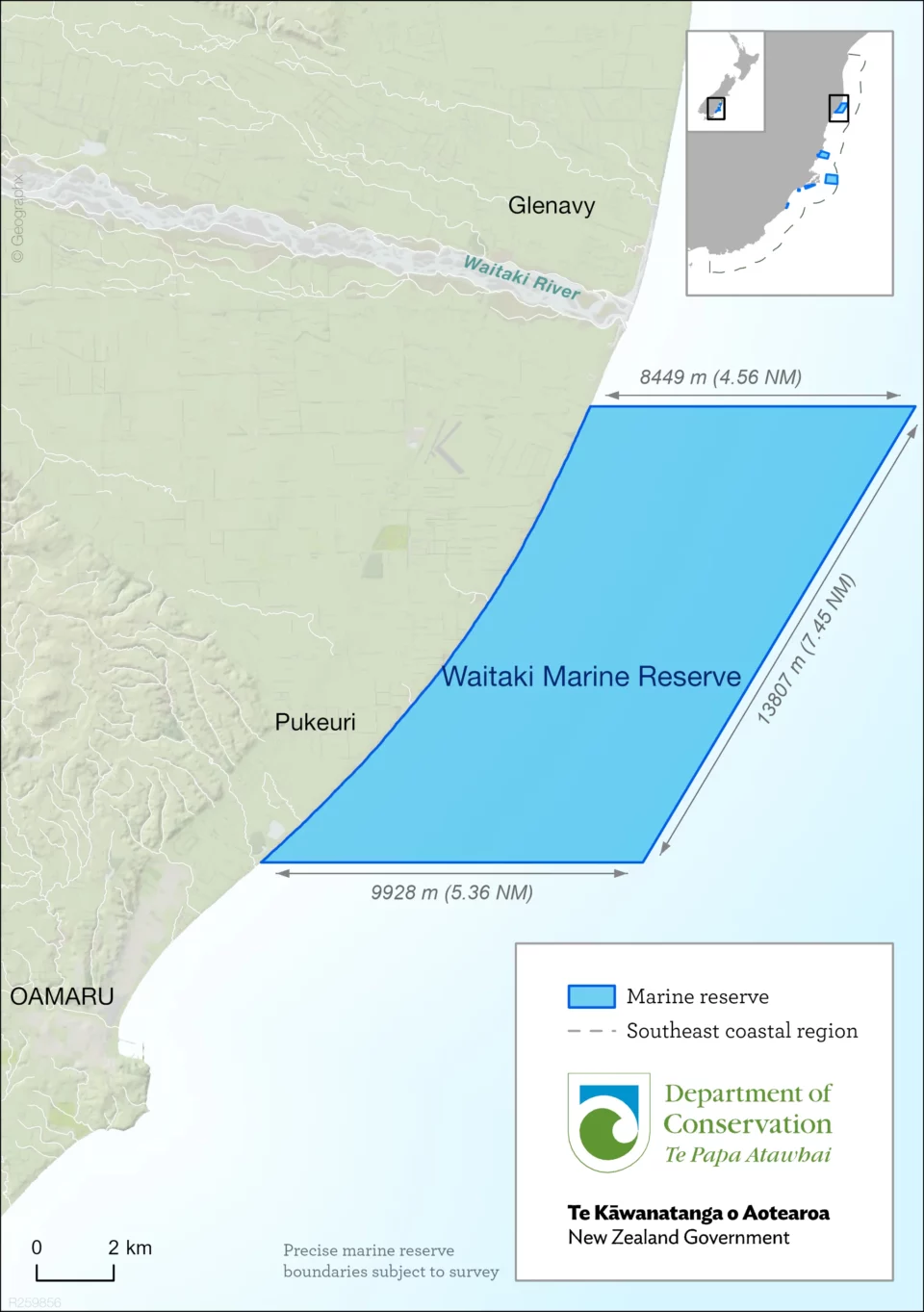

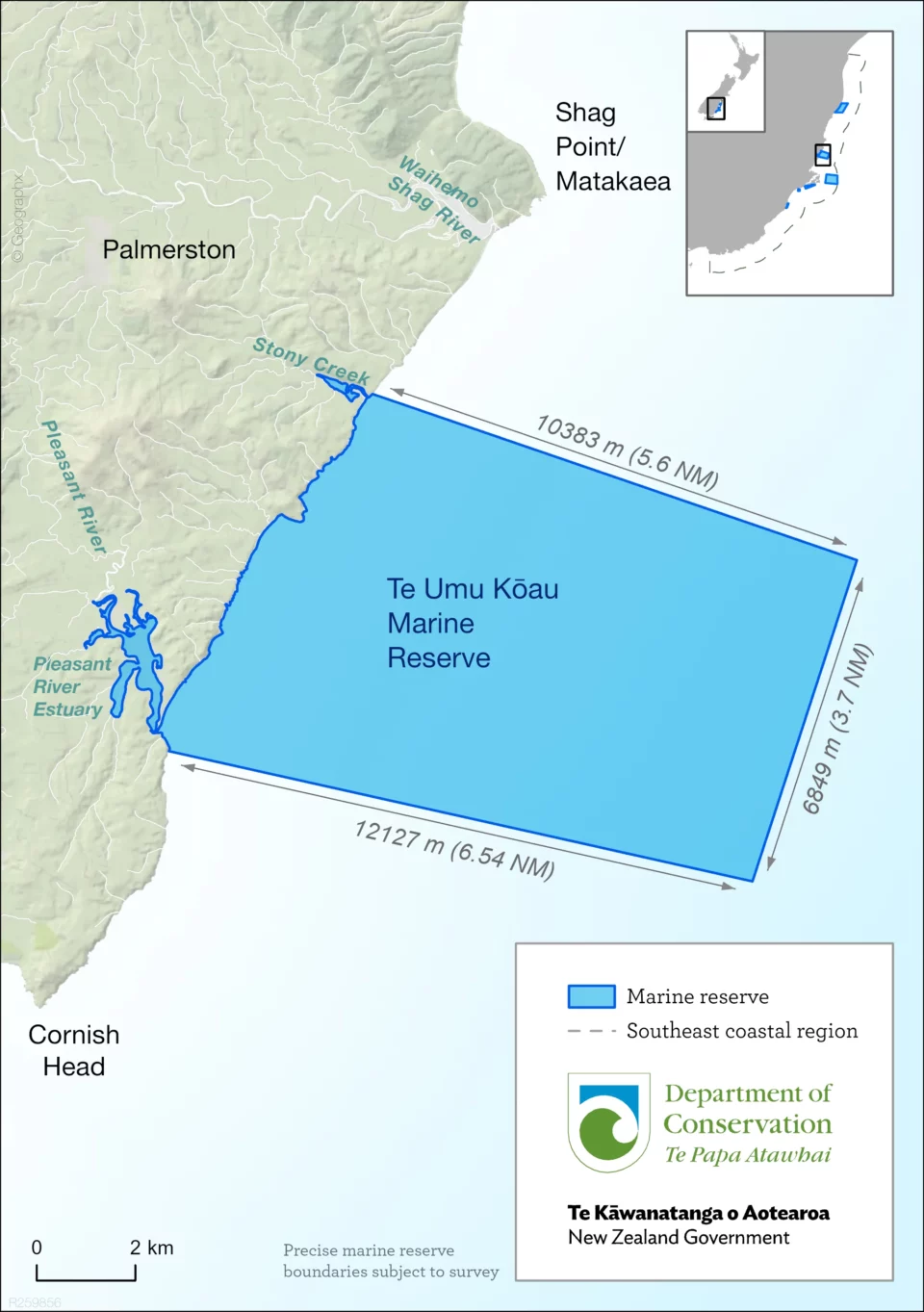

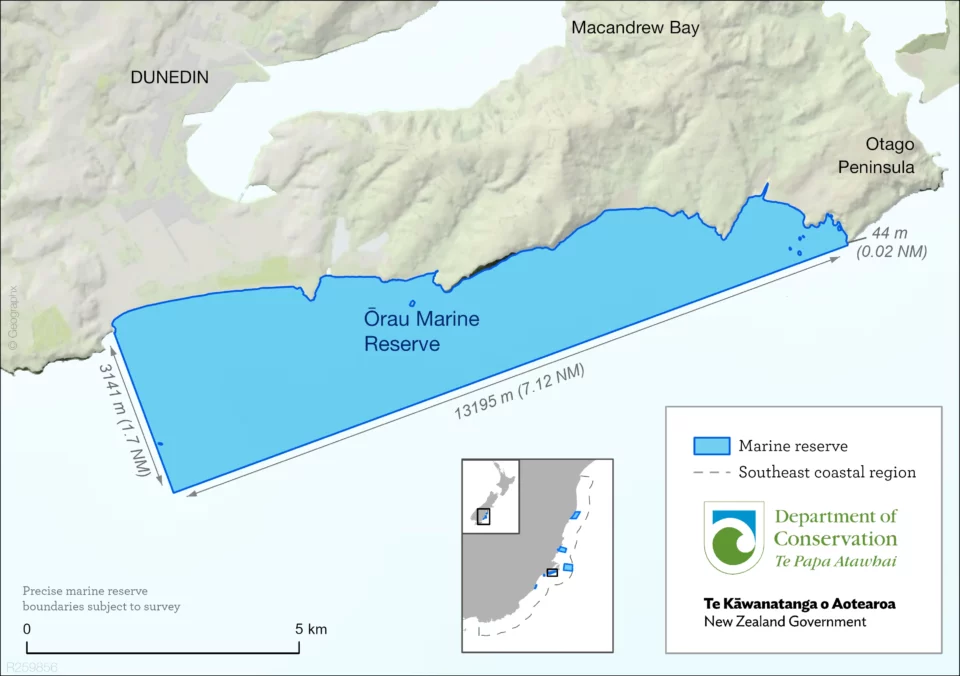

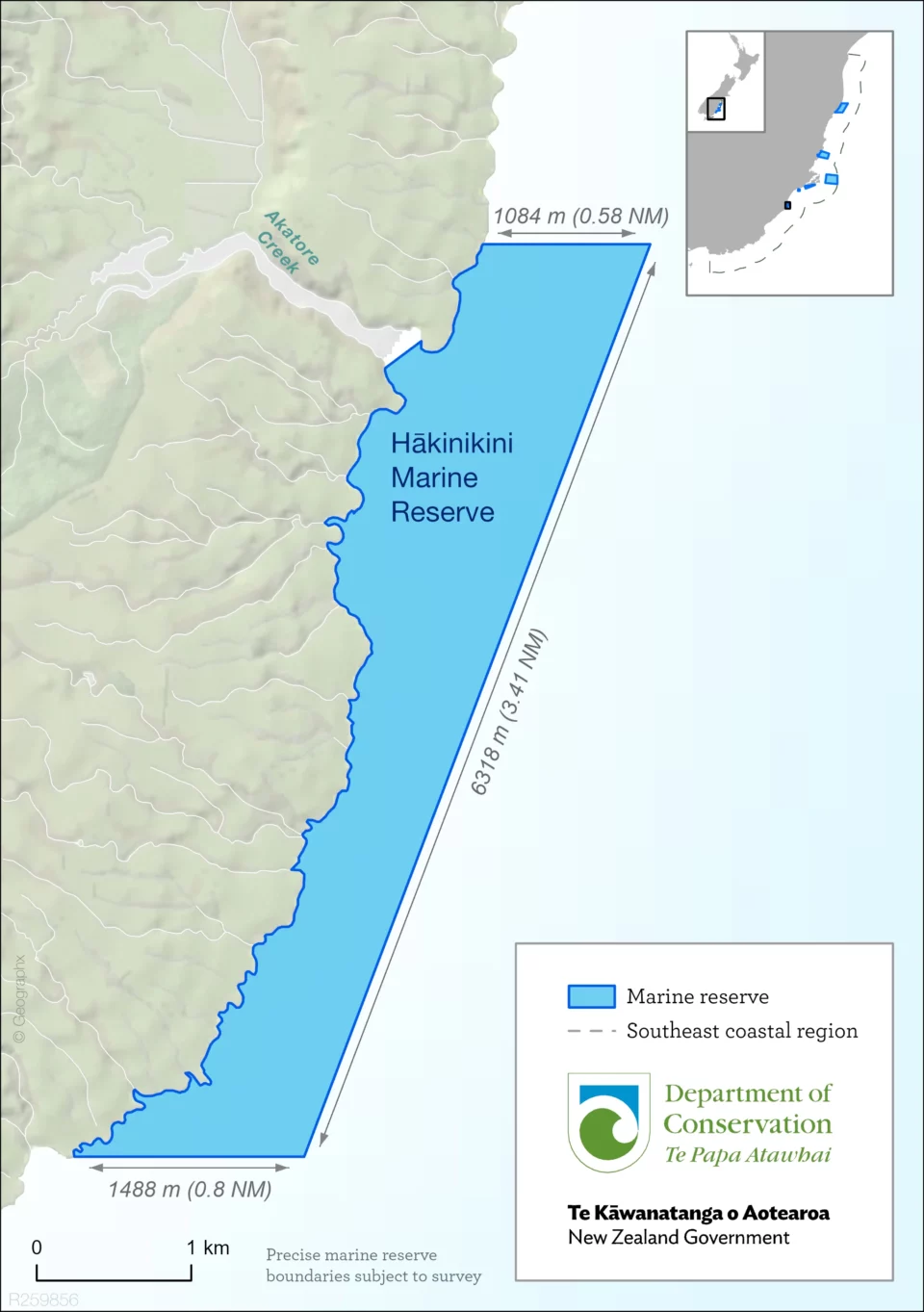

In early October this year, the Department of Conservation (DOC) announced six new marine reserves to be the first established along the southeastern coast of the South Island.

These six new marine reserves will increase mainland reserves by 67% – from 615 km2 to 1,011 km2. Dotted from Oamaru to the Catlins they aim to protect the habitats of hoiho/yellow-eyed penguin, toroa/northern royal albatross, pakake/New Zealand sea lion, as well as brittle stars, squat lobster, kōura, shrimps, crabs, sponges, sea squirts, reef fishes and many others.

The announcement was made in Dunedin by Conservation Minister Willow-Jean Prime and Oceans and Fisheries Minister Rachel Brooking, joined by Kāi Tahu representatives.

The marine reserves include estuarine and tidal lagoons, rocky reefs, offshore canyons, giant kelp forests and deepwater bryozoan or lace coral thickets, and an array of marine life that were under pressure from human activity. The result comes from more than a decade of work by local communities and stakeholders.

Prime said close engagement with mana whenua had been important.

“I acknowledge Kāi Tahu – as kaitiaki for this spectacular coast – for their engagement in the shaping of the new marine reserves,” she said. “Provisions have been made for Kāi Tahu to continue to access the marine reserve areas for practices that enhance their mātauraka Māori (traditional knowledge) and retrieve koiwi tākata (ancestral remains), artefacts and marine mammal remains.”

Prime added that Kāi Tahu would work in partnership with the Department of Conservation to manage the marine reserves once they were in place.

Brooking said the six marine reserves were the first step in creating a network of marine protection in the area.

“You can’t have a successful commercial fishing industry in an unhealthy ocean,” Brooking explains.

She said 90% of the more than 4,000 submissions had shown there was broad backing for the proposed network.

Dunedin surfer Dr Tim Ritchie was part of the 10-year southeast marine protection (SEMP) process and said it had been a long, and frustrating experience.

“The idea that every stakeholder group would come together in some kind of unanimous harmony was optimistic, to say the least,” Ritchie explains. “Our marine reserve network is far smaller and less effective than it could have been, primarily due to the pressure and lobbying of commercial fishing interests.”

“Our marine reserve network is far smaller and less effective than it could have been, primarily due to the pressure and lobbying of commercial fishing interests.”

Chanel Gardner, who represents Harbour Fish in Otago, said they, as marine users and suppliers of seafood to their communities, loved the concept of a marine reserve.

“Protecting at-risk fish species, habitats and biodiversity are hugely important as well as meeting our international obligations as a convention and treaty member country,” Gardner explains. “We are just sad that these marine reserves have been actioned in an area where we have none of those issues or pressures that the Marine Reserves Act seeks to fix.”

She said they had always been a “nice to have” here, especially when compared with the pressures faced in the Hauraki Gulf and Kaikoura from irresponsible recreational fishing, localised depletion and environmental impacts from land-based activities.

“Our Otago marine area does not need the protection that the marine reserves provide,” Gardner adds. “But if we were to do it, the government ought to do the right thing by the community and implement something great.”

Gardner said the new marine reserves will have a direct impact on their business.

“There are hardly any commercial fishers left so they have less area and have to expend more effort to get the fish they usually would,” she explains. “And remember, not all fish move around all the time and like to stay in their habitats. If an area is closed, that minimises the fish available for the community to buy and if fishers have to go further to get fish that they would usually get easily you’d think that’s less than ideal from a sustainability point as well.”

“Our Otago marine area does not need the protection that the marine reserves provide. But if we were to do it, the government ought to do the right thing by the community and implement something great.”

Gardner said it was not just commercial fishers, recreational fishers, or surfers, who were affected.

“We are all part of a very small community that uses the Otago marine space and some of those groups do a couple of those things,” she continues. “What affects one ‘group’ actually impacts us all in a place like Dunedin.”

Ritchie recalls a meeting with one of the larger recreational fishing groups involved in the consultation.

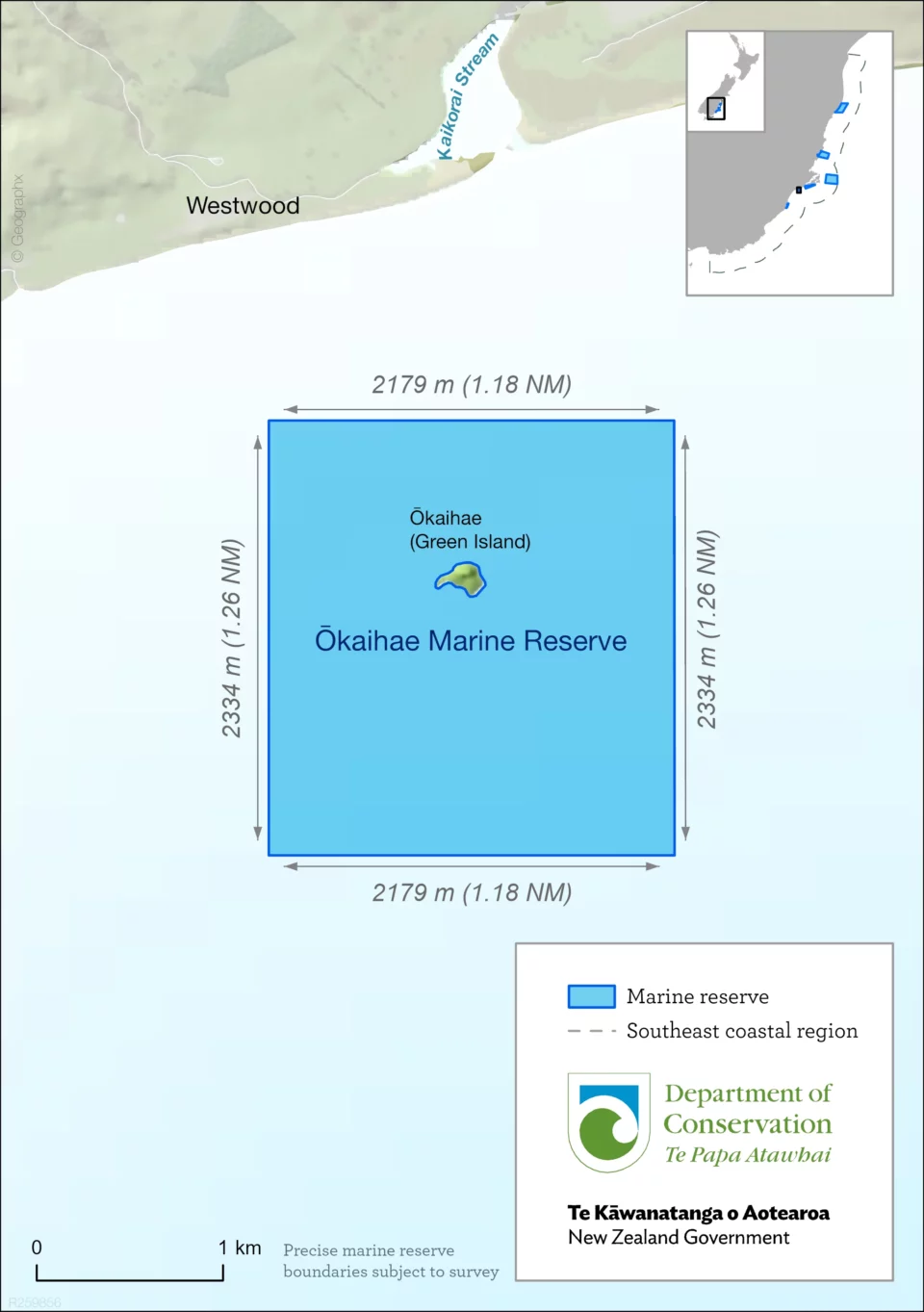

“One of the highlights of our process for me was fronting up to a meeting called by the Green Island Fishing Club,” Ritchie shares. “They wanted to know what we were up to because someone had got wind of the proposed Ōkaihae (Green Island) Marine Reserve.”

That meeting was held at a pub with about 100 club members present.

“I thought we were going to get lynched,” Ritchie remembers. “We put a map up on the wall and then worked our way down the coast pointing out the various proposed marine reserves. We got to the Ōkaihae Marine Reserve and explained our thinking behind the 5km2 area proposed around Green Island. There was silence. Then the scraping of a chair as a large gentleman dressed in camo gear stood up. We braced ourselves …”

“‘I reckon that’s a fucken good idea,’ he boomed. ‘We’ve fucked it out there, so I’m all for the reserve.’”

“He was joined in agreement by various other club members and we all breathed a sigh of relief,” laughs Ritchie.

“‘I reckon that’s a fucken good idea. We’ve fucked it out there, so I’m all for the reserve.’”

Gardner said the main point of contention from the commercial fishing viewpoint was the location of the reserves.

“Thousands of people submitted on these, but only iwi had any say on moving boundaries,” Gardner offers. “Iwi are important, of course, but the other marine users had important things to add that would have been helpful for everyone. For example, if they had moved one reserve 500m then important crayfish grounds could still be fished. But DOC didn’t entertain any submissions for adjustments from any sector.”

Gardner believes this could have been a marine reserve system that didn’t impact our ocean users, but achieved all of DOC’s biodiversity goals.

“Instead they did a system that only pleases the people who do not use our marine area trying to improve some marine reserve stats,” she claims. “Why should people in Wellington have a say over what we do in our bit of the ocean when we are proven as good custodians?”

Gardner raised questions about the timing of the announcement being within a week of the election.

She hoped the next government would review the proposed system and at the next step towards legal implementation they would legitimately listen to the community and take their advice on what could be better for everyone’s objectives.

“They haven’t listened to date and have imposed what they believed to be good without listening to any of us on the water.”

DOC Director Office of Regulatory Services, Sarah Owen, said the SEMP process was initiated under a former National Government, when the Minister of Conservation, the Hon Nick Smith, announced the process in 2013.

The SEMP Forum was appointed in 2014 and completed its work in 2018.

“There are many New Zealanders who have participated in and provided their views between 2018 and 2023 on the SEMP proposals,” explains Owen. “And Ministers took these views into consideration in their decision-making process, as required by law.”

Under the Marine Reserves Act (1971), the decisions made by the Minister of Conservation are final.

Owen said the next steps were administrative and included the making of the Orders in Council (for the six marine reserves).

The marine reserves come into force after the Executive Council-approved Orders in Council are Gazetted and 28 days have passed.

Dr Chris Hepburn works at the University of Otago in the Department of Marine Science as a professor in marine science. His research focus is on kelp forest, and coastal fisheries and he is also involved in customary fisheries.

He said the SEMP forum included three commercial fisheries representatives.

“Do you think we would have put the marine reserves there if we had a choice as scientists?” Hepburn asks. “We wouldn’t have put them there. The reason they are there is because it is a political thing, right? And it has included them.”

He said a great example was that Tow Rock was initially going to be within the Ōrau Marine Reserve.

“We didn’t put it in because of the commercial interest,” he shares. “We had to cut through the reef knowing that it’s a terrible management thing to do. We had to because we were protecting these fisheries and the jobs that they have.”

Hepburn said he didn’t believe the commercial fishermen really wanted the reserves overturned.

“It would be silly.”

“We had to cut through the reef knowing that it’s a terrible management thing to do. We had to because we were protecting these fisheries and the jobs that they have.”

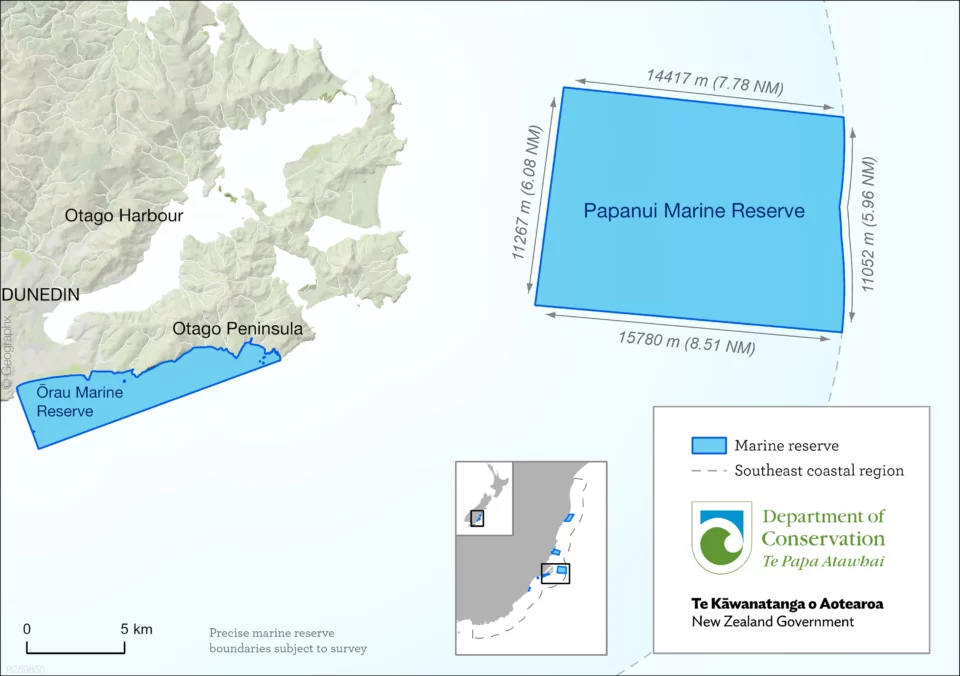

Ritchie agreed that the Ōrau Marine Reserve carried a flaw that stemmed from compromises.

“Unfortunately we broke one of the golden rules of marine reserve design, which is to not run boundaries through the middle of reef systems,” Ritchie offers. “The rationale is that mobile species are able to be caught on the portion of the reef outside the reserve, which decreases the recovery potential for these species inside the reserve. We broke this rule near the eastern boundary of the Ōrau Marine Reserve by excluding Tow Rock and its surrounding reef which connects through with the reef contained within the reserve.”

Ritchie said Tow Rock was excluded from the reserve because of the pressure from the crayfishing industry.

“It’ll be interesting to see what the effect of this compromise has on the recovery of the species within the Ōrau Marine Reserve.”

If we look at established marine reserves like those in the North Island; The Poor Knights and Leigh Marine Reserve then we see fascinating and vibrant ecosystems with a spillover effect for the fishery.

“While fishing is not the primary rationale for marine reserves,” Ritchie offers. “Science demonstrates that marine reserves can improve nearby fishing via the mechanism of species spillover across marine reserve boundaries.”

Gardner challenges the balance in this process.

“Ecosystems are complex beasts and often fishing can improve in some areas,” Gardner begins. “But equally a reserve can disrupt the status quo of an area and lead to some species flourishing that have the ability to dominate an ecosystem.”

She warned that the unintended consequences of plopping reserves around arbitrarily, “given the final decisions are almost a decade after the initial science was done”, could be quite huge and not all beneficial.

“The other interesting difference with reserves like The Poor Knights is that people can access those reserves,” she explains. “Down here we have hardly anyone (comparatively) who can access and take their boats greater distances. Many of our rec guys are close inshore.”

Gardner questioned whether safety for recreational fishermen would become an issue for those fishing further from safe harbours, as well as for those who may have to enact rescues.

That has also been raised as a concern by the Otago surf community, many of whom launch their IRBs and jet skis from beaches within the soon-to-be-instated Ōrau Marine Reserve to reach their fishing spots. To launch outside the marine reserve would involve long hauls through changeable and often treacherous conditions. That would make it very difficult to reach the lesser-fished spots, outside the reserve boundaries.

Owen said this was not the case.

“Vessels including smaller IRBs and jet skis are allowed to travel through a marine reserve with fish onboard caught in adjacent areas,” she explains. “This is the case for all existing marine reserves around New Zealand and will also apply to the six new marine reserves once they are formally in place.”

Owen went on to explain that the transit, shelter and anchoring of boats within a marine reserve was also allowed, although when anchoring it was a legal requirement to keep damage to the minimum practicable level.

The local surf community also raised questions about what a thriving marine reserve in 10-20 years might mean for shark populations. Given that more than a dozen regularly surfed waves occur within Ōrau Marine Reserve alone, it is a fair question.

Would there be a corresponding increase in sharks?

“Overall, the answer to your question is no,” explains shark expert Dr Riley Elliott.

“All logic would point to the fact that if there was more local and natural prey around, that this would reduce the likely risk of adverse interactions with sharks anyway.”

Elliott said that while marine reserves could increase fish life, and thus possibly the predators of that marine life, it was generally actually the other way around: when large sharks were protected, the ecosystem below them came back.

“An example being Beqa Lagoon area in Fiji, where bull sharks were protected and the reef ecosystem below them flourished,” he explains.

Elliott said that even if these reserves in New Zealand did massively increase species abundance, the small local scale of it would not be enough to attract and create residency of shark species relevant to the area, like great whites.

“Great Whites are highly migratory and feed on seasonal prey spanning from the seal colonies down south, to the tuna and reef species of the tropics,” Elliott shares. “Small-scale marine reserves would not cause such migratory species to reside.”

He added that the absence of bull sharks in New Zealand, which do have a small home range, eliminated the possibility of them increasing locally in abundance, thus potentially causing increased risk.

“However where increases in bull shark numbers in marine reserves have occurred, like that in Beqa, Fiji, there has been no such risk associated with population increase,” Elliott reports. “The only other common shark species in the Otago region is the seven-gill shark and that would not pose increased risks from marine reserves.”

“The only major risk regarding sharks in this region are from great whites, and that risk is vastly reduced if you avoid overlapping with high densities of seals,” Elliott concludes.

“The only major risk regarding sharks in this region are from great whites, and that risk is vastly reduced if you avoid overlapping with high densities of seals.”

While these are Otago’s first marine reserves, they are not the first attempt at protecting the marine environment.

“Talk to any of the divers that dived before the 1980s and they will tell you just how prolific marine wildlife once was,” explains Dive Otago owner Virginia Watson. “In the 1970s crayfish lined the beams of the wrecks at Aramoana, but by the 1980s the stocks had been depleted so much, there were virtually no crayfish left, and the fish stocks were dropping.”

She said a boom in the popularity of gathering kaimoana and spearfishing had led to this significant drop in the marine populations.

“In response, the diving clubs of Ōtepoti decided to work together in order to protect the ocean’s future,” Watson recalls. “They realised that dive practices at that point were over-exploiting the marine environments. Collectively, they decided to designate the south-east side of Aramoana Mole as a voluntary marine reserve, meaning that club members and anyone who chose to observe the guidelines would not take marine life or gather kaimoana from that side.”

Otago Harbour Board, Otago Underwater Club, Otago University Underwater Club, which was New Zealand’s first university dive club, Southern Sea Divers and Aramoana Divers were all signatories to the agreement.

“It was never an ‘official’ marine reserve, nor was it ever intended to be one,” explains Watson. “Members’ agreements are just that; an extension of local etiquette, similar to tikanga and practices such as rahui practised by mana whenua, which are also supported by the local dive community. Being voluntary meant that it reduced the impact but allowed the people of Aramoana and mana whenua to have a healthy resource that could still be freely used.”

Over time the voluntary nature of the reserve at Aramoana Mole eroded.

“Voluntary reserves used to be quite strong back when I started diving, but some people don’t respect them,” offers Hepburn. “I reckon 80 per cent of people do the right thing, but then the 20 per cent start doing it and then everyone else sees that and they’re like, ‘well if they are doing it well, what’s the point?’ I believe that’s probably what has happened at the Mole. I know a lot of people spearfish out there now, and no one used to.”

Watson acknowledged that if we wanted reserves to support future generations and to share with our young it had to be in someone’s backyard.

“Just because a practice is voluntary, doesn’t mean there is no value in the practice,” she offers. “A healthy society encourages communities, clubs, businesses, groups and individual whānau to develop practices, guidelines, rules and tikanga in response to local challenges. In this way, we are empowered to govern and manage the spaces we call home.”

Watson said she was happy with the outcome of the new marine reserves, although she had hoped to see one that would be easily accessible so tamariki could witness an undisturbed ecosystem.

“For a long time, divers in the south have travelled to other marine reserves in the north for enjoyment,” Watson adds. “It feels good that we are now, as a region, doing our bit. We look forward to seeing the positive impacts that we know marine reserves bring over time.”

“It was never an ‘official’ marine reserve, nor was it ever intended to be one. Members’ agreements are just that; an extension of local etiquette, similar to tikanga and practices such as rahui practised by mana whenua, which are also supported by the local dive community.”

Local iwi also have a handful of effective tools in the chest when it comes to marine protection. These include taiāpure, which restricts recreational take, mātaitai, which restricts recreational and commercial take, and rāhui, which can restrict take and even activities, such as in the event of a death along the coast.

The Taranaki surf coast is currently under a no-take rāhui to encourage the recovery of the fishery.

“From a customary perspective they are really useful tools that are also responsive,” Hepburn explains. “The East Otago Taiāpure is a good example of that.”

Brendan Flack is a tangata tiaki for Kāti Huirapa ki Puketeraki and lives at Puketeraki. He is the chairman of the East Otago Taiāpure, which was established around 1999 after a decade of struggle to have customary rights recognised in legislation.

“It was a difficult process, but after a generation of hard work by an inclusive committee we now have a fishery that is slowly rebuilding,” Flack explains. “The Marine Protection Areas are different, but we have the opportunity for revolutionary management in Otago.”

Flack said the taiāpure and mātaitai were responsive, with mechanisms, such as changing regulations or bylaws, to either allow or prohibit activities.

“At the time when the East Otago Taiāpure was established that was the only mechanism available to tangata whenua,” Flack adds.

Hepburn has been a member of the East Otago Taiāpure committee since 2008.

He said they had really struggled for a long time to protect the fisheries along the coast.

“People who have rights to 10 pāua per day,” Hepburn shares. “Well, really that model doesn’t work. The taiāpure has allowed us to actually move to a space where we can actually say, ‘Well, yes, this reef is able to sustain a thousand pāua coming off it a year, so, therefore, that’s what gets taken off it’. Rather than, ‘Oh, we’re getting 10 per day, oh, and that doubled to 30 more people than we had last year. We’ve just lost a thousand more pāua than we thought we did’. The taiāpure is a good model.”

“Taiāpure and mātaitai are both managed by mana whenua,” Flack shares. “The one that we’re talking about is managed by Kāi Tahu, but it includes community. It’s an inclusive management regime – it’s certainly not exclusive.”

Ōtākou Rūnaka also manages a mātaitai near the entrance to Otago Harbour, which includes a large part of the harbour and extends to include the eastern side of Aramoana Mole.

Flack describes the East Otago Taiāpure as a shared fishery.

“You’ve got recreational, commercial, and customary,” he explains. “Customary take is allowed for under the Fisheries Act, and that’s either inside, or outside a customary protected area. Customary take in a Taiāpure is really restricted. One of the key principles of fisheries is manaakitanga. So that means that it’s not exclusively for Ngāi Tahu, or for mana whenua – it’s about hosting your visitors well. Customary authorisations are not exclusively just for Māori, they can be issued to anyone. It’s up to the fisheries managers, the tangata tiaki, to make those calls and each area has different needs.”

“I’ve had it described as tangata tiaki, customary fisheries managers, can essentially rewrite fisheries law every time they use the authorisations,” Flack elaborates. “When we put a rāhui on an area we’ve generally already stopped our customary take. We take the lead and show an example of fisheries restoration.”

“When we put a rāhui on an area we’ve generally already stopped our customary take. We take the lead and show an example of fisheries restoration.”

He said there was a rāhui on the taking of pāua, attached kelp and set-netting in the East Otago Taiāpure and that applied to everybody including commercial fishermen.

“It lasts until the tangata tiaki assess, through surveys, that the population has become healthy again.”

Flack said they never want to close a fishery because that would also be the end of mātauranga.

“If it’s closed up forever then that’s the end of any traditional knowledge that goes with it,” Flack explains. “Then you start reading all the knowledge in books and in stories and not in the actual doing. That’s the kind of thing that a taiāpure allows us to do in managing a fishery in that way. I would say too, that we’ve recognised that we’re in a period of rebuilding and restoring the fishery. So, we’ve restricted our activities accordingly – we’re finding that restoration is key. Before it gets absolutely destroyed you need that restoration to take place again. And then you can’t go back to bag limits or quota. You must manage it under these authorisations – this is, in my opinion, the way forward with a local fishery like we’re talking about.”

Hepburn agreed and said ecosystem-based fishery models made more sense.

“As a scientist kaitiakitanga makes sense – it’s not an economic model,” he continues. “Fisheries aren’t an economic model – they’re complex – there’s a whole range of different things at play.”

“As a scientist kaitiakitanga makes sense – it’s not an economic model. Fisheries aren’t an economic model – they’re complex – there’s a whole range of different things at play.”

Hepburn said that while mātaitai and taiāpure were great fisheries management tools, we needed to remember that they were actually redress for treaty breaches.

“People ask why can’t everyone else have one? And that’s kind of the reason,” he adds. “It would be great if our fisheries could be effectively managed by the quota management system. But really, because coastal fisheries are so complex, it’s really hard to manage at that higher level. It is a bit of a complex one, but all power to Ngāi Tahu and the mātaitai for getting support around it because, in the end, those benefits flow to us. I’m not Māori, but I think that’s the future.”

Flack believes the time is overdue for some sort of protection alongside co-management.

“Having, Ngāi Tahu managing and having wānanga being involved in the assessment of the success, or the efficacy of the reserves – I think that’s groundbreaking – for us to be out there monitoring,” he claims.

Flack said Kāti Huirapa, their whanau, supported in principle and understood the need for marine reserves, but in a way that did not extinguish their fishery settlement.

“It was a 10-year process,” he admits. “The ministries were wanting stuff done tomorrow, kind of thing. And we reacted as quickly as we possibly could without undermining the generations that will follow. It certainly wasn’t taken lightly.”

“I love fishing,” asserts Hepburn. “I can go and fish at 30 places that I could go and fish before. I’ve got two spots I can’t now. Sometimes it’s nice to go to a place just to look and learn about all the different things. We do need to adjust our view – no one’s lost anything. Green Island has been hammered, I’ve been diving there since the early 2000s. It’s just been hammered and that’s the place that I think will be absolutely incredible. That’s our Poor Knights right there for diving.”